What is innovation? I don’t know, but then I’m not even sure that it’s an interesting question. The yearning so many companies have to be innovative often seems to prevent them from actually doing anything innovative. They get so caught up in trying to come up with the next innovation — the next big product — that they often fail to do anything innovative at all. It’s more productive to define innovation by understanding what it’s not: doing the same thing as the rest of the crowd, while accepting that there are no silver bullets and that you don’t control all the variables.

So, what is innovation? This seems to be a common question thats comes up whenever a company wants to innovate. After all, the first step in solving a problem is usually to define our terms.

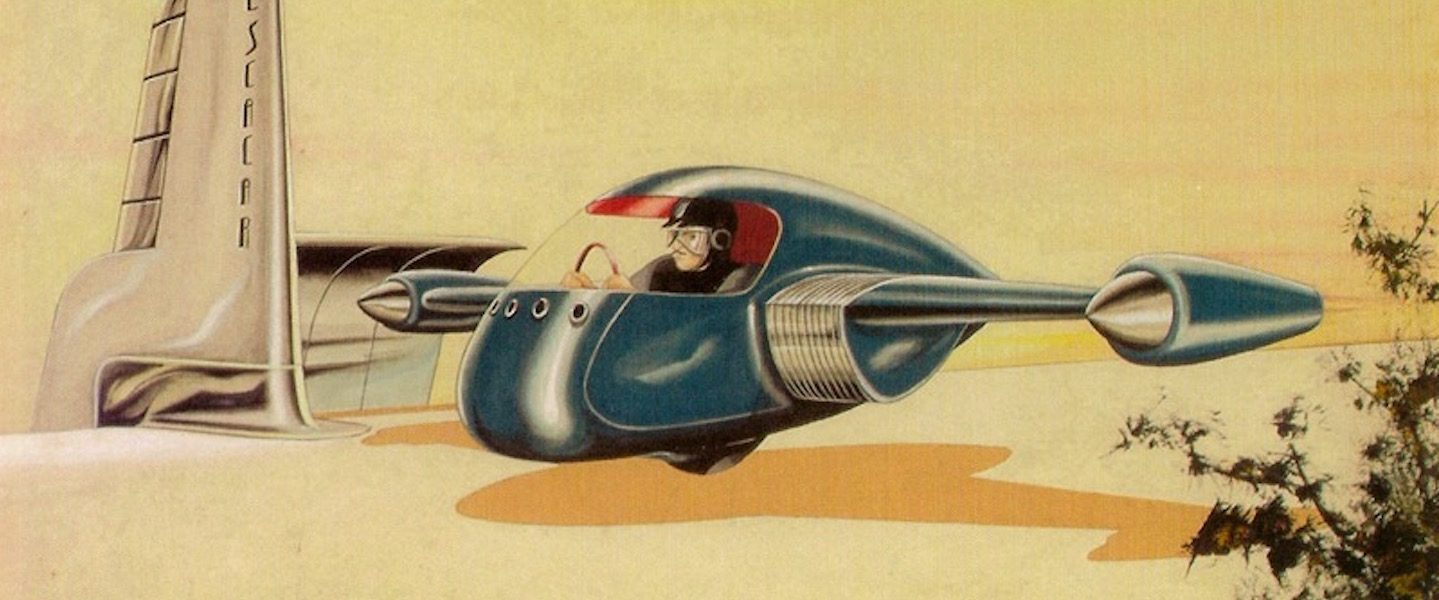

Innovation is a bit like quantum theory’s spooky action at a distance,[ref]Spooky action at a distance? @ Fact and Fiction[/ref] where stuff we know and understand behaves in a way we don’t expect. It can be easy to spot an innovative outcome (hindsight is a wonderful thing), but it’s hard to predict what will be innovative in the future. Just spend some time browsing Paleo-Future[ref]Paleo-Future[/ref] (one of my favourite blogs) to see just how far off the mark we’ve been in the past.

The problem is that as it’s all relative; what’s innovative in one context may (or may not) be innovative in another. You need an environment that brings together a confluence of factors — ideas, skills, the right business and market drivers, the time and space to try something new — before there’s a chance that something innovative might happen.

Unfortunately innovation has been claimed as the engine behind the success of more than a few leading companies, so we all wanted to know what it is (and how to get some). Many books have been written promising to tell you exactly what to do to create innovation, providing you with a twelve step program[ref]Twelve step programs @ Wikipedia[/ref] to a happier and more innovative future. If you just do this, then you too can invent the next iPhone.[ref]iPhone — the Apple innovation everyone expected @ Fast Company[/ref]

Initially we were told that we just needed to find the big idea, a concept which will form the basis of our industry shattering innovation. We hired consultants to run ideation[ref]Ideation defined at Wikipedia[/ref] workshops for us, or even outsourced ideation to an innovation consultancy asking them to hunt down the big idea for us. A whole industry has sprung up around the quest for the big idea, with TED[ref]TED[/ref] (which I have mixed feelings about) being the most obvious example.

As I’ve said before, the quest for the new-new thing is pointless.[ref]Innovation should not be the quest for the new-new thing @ PEG[/ref]

The challenge when managing innovation is not in capturing ideas before they develop into market shaping innovations. If we see an innovative idea outside our organization, then we must assume that we’re not the first to see it, and ideas are easily copied. If innovation is a transferable good, then we’d all have the latest version.

Ideas are a dime a dozen, so real challenge is to execute on an idea (i.e. pick one and do something meaningful with it). If you get involved in that ideas arms race, then you will come last as someone will always have the idea before you. As Scott McNealy at Sun likes to say:

Statistically, most of the smart people work for somebody else.

More recently our focus has shifted from ideas to method. Realising that a good idea is not enough, we’ve tried to find a repeatable method with which we can manufacture innovation. This is what business does after all; formalise and systematise a skill, and then deploy it at huge scale to generate a profit. Think Henry Ford and the creation of that first production line.

Design Thinking[ref]Design Thinking … what is that? @ Fast Company[/ref] is the most popular candidate for method of innovation, due largely to the role of Jonathan Ive[ref]Jonathan Ive @ Design Museum[/ref] and design in Apple’s rise from also-ran to market leader. There’s a lot of good stuff in Design Thinking — concepts and practices anyone with an engineering background[ref]Sorry, software engineering doesn’t count.[/ref] would recognise. Understand the context that your product or solution must work in. Build up the ideas used in your solution in an incremental and iterative fashion, testing and prototyping as you go. Teamwork and collaboration. And so on…

The fairly obvious problem with this is that Design Thinking does not guarantee an innovative outcome. For every Apple with their iPhone there’s an Apple with a Newton.[ref]The story behind the Apple Newton @ Gizmodo[/ref] Or Microsoft with a Kin.[ref]Microsoft Said to Blame Low Sales, High Price for Kin’s Failure @ Business Week[/ref] Or a host of other carefully designed and crafted products which failed to have any impact in the market. I’ll let the blog-sphere debate the precise reason for each failure, but we can’t escape the fact the best people with a perfect method cannot guarantee us success.

People make bad decisions. You might have followed the method correctly, but perhaps you didn’t quite identify the right target audience. Or the technology might not quite be where you need it to be. Or something a competitor did might render all your blood sweet and tears irrelevant.

Design Thinking (and innovation) is not chess: a game where all variables are known and we have complete information, allowing us to make perfect decisions. We can’t expect a method like Design Thinking to provide an innovative outcome.

Why then do we try and define innovation in terms of the big idea or perfect methodology? I put this down to the quest for a silver bullet: most people hope that there’s a magic cure for their problems which requires little effort to implement, and they dislike the notion that hard work is key.

This is true in many of life’s facets. We prefer diet pills and magic foods over exercise and eating less. If I pay for this, then it will all come good. If we just can just find that innovative idea in our next facilitated ideation workshop. Or hire more designers and implement Design Thinking across our organisation.

Success with innovation, as with so many things, is more a question of hard work than anything else. We forget that the person behind P&G’s Design Thinking efforts,[ref]P&G changes it’s game @ Business Week[/ref] Cindy Tripp, came out of marketing and finance, not design. She chose Design Thinking as the right tool for the problems she needed to solve — Design Thinking didn’t choose her. And she worked hard, pulling in ideas from left, right and centre, to find, test and implement the tools she needed.

So innovation is not the big idea. Nor is it a process like Design Thinking.

For me, innovation is simply:

- working toward a meaningful goal, and

- being empower to use whichever tools will be most beneficial.

If I was to try and define innovation more formally, then I would say that innovation is a combination of two key concepts: obliquity[ref]Obliquity defined at SearchCRM[/ref] and Jeet Kune Do’s[ref]Jeet Kune Do, a martial art discipline developed by Bruce Lee @ Wikipedia[/ref] concept of absorbing what is useful.

Obliquity is the simple idea that the best way to achieve a goal in a complex environment is to take an indirect approach. The fastest and most productive path to the top of the mountain might be to take the path that winds its way around the mountain, rather than to try and walk directly up the steepest face.

Apple is a good example of obliquity in action. Both Steve Jobs and Jonathan Ives are on record as wanting to make “great products that we want to own ourselves,” rather than plotting to build the biggest and most innovative company on the planet. Rather than try and game the financial metrics, they are focusing on making great products.

Bruce Lee[ref]Bruce Lee: the devine wind[/ref] came up with the idea of “absorbing what is useful”[ref]Absorbing what is useful @ Wikipedia[/ref] when he created Jeet Kune Do. He promoted the idea that students should learn a range of methods and doctrines, experiment to learn what works (and what doesn’t work) for them, “absorb what is useful” while discarding the remainder. The critical point of this principle is that the choice of what to keep is based on personal experimentation. It is not based on how a technique may look or feel, or how precisely the artist can mimic tradition. In the final analysis, if the technique is not beneficial, it is discarded. Lee believed that only the individual could come to understand what worked; based on critical self analysis, and by, “honestly expressing oneself, without lying to oneself.”

Cindy Tripp at P&G is a good example of someone absorbing what is useful. Her career has her investigating different topics and domains, more a sun shaped individual than a t-shaped one.[ref]T-Shaped + Sun-Shaped People @ Logic + Emotion[/ref] Starting from a core passion, she accreted a collection of disciplines, tools and techniques which are beneficial. Design Thinking is one of these techniques (which she uses as a reframing tool).

I suppose you could say that I’ve defined innovation by identifying what it’s not: innovation is the courage to find a different way up the hill, while accepting that there are no silver bullets and that you don’t control all the variables.

Updated: Tweeked the wording in the (lucky) 13th paragraph in line with Bill Buxton’s comment.

For every Apple with their iPhone there’s an Apple with a Newton. Or Microsoft with a Kin.

This is one of the most sensible articles I've seen on innovation in ages. Thanks so much!

My own take on innovation is that innovation always solves a problem. If not, it will inevitably create one. And each time you consider a solution, you need to reflect on the cultural, political, and technological consequences of your action.

Bill Buxton, a Microsoft scholar, has a great story about just this in which he describes how the Enfield folks developed a breach-loading rifle that almost cost the British most of their empire back in the 1850s. There was a video available of this story, but I cannot find it now.

Basically, Enfield developed small pre-measured packets of gunpowder that could be torn open with the teeth and poured directly into the breach of the gun. The paper was greased so that the powder remained dry.

But who were the British fighting against (and alongside) back in the 1850s? Hindi and Muslims. And what was the paper greased with? Animal fat from pigs and cows. The result? The weapon worked brilliantly, but the non-English troops revolted – a Hindu or a Muslim does NOT want to put anything associated with a pig or a cow near the mouth! So, a technological innovation was a failure because it did not take into account cultural needs and nearly led to dire political consequences for the British.

I don't know if you've seen my own work in this area, but there are a couple of presentations on innovation on Slideshare. There were also videos on Brightcove, but I think these have disappeared. Here's a working Slideshare link:

http://www.slideshare.net/ericreiss/reiss-on-in…

My own main point is that invention is often mistaken for innovation. Actually, I see a clear progression from invention to innovation to best practice. And the next period of innovation often builds on previously determined best practices. I suspect this is one of the reasons design thinking goes wrong – designers insist on thinking outside the box whereas innovation sometimes serves just as creatively by making a box bigger and better.

[…] What is innovation? (tags: innovation) […]

Nice Bill Buxton story Eric!

I’m struggling these days to understand how to define innovation other than retrospectively (isn’t hindsight a wonderful thing). We can pin down invention, customer need, product development, marketing etc. — all the elements to make an innovation successful — but picking an innovation seems the impossible task.

Efforts to define and codify innovation are like capturing lightening in a bottle. You can’t systematise a process which has a large degree of luck to it. What you can do, though, is to be prepared. This is where tools like design thinking fit in.

The model I like for innovation is the approach to basket ball described by The no-stars all star. Understand the inputs, spend your energy wisely, and realise that this is a numbers game which requires a great deal of luck.

You don’t have to be retrospective, you just need to evaluate potential solutions before you implement them. And as I said, innovation always solves a problem. That’s why “picking” an innovation isn’t really hard at all. You can analyse most of this before implementation. As to the moniker itself, well, yes, this is retrospective. An “innovation” only becomes one when it has proven its worth.

I like this piece in that it does a nice analysis, and at the same time, opens the door for a deeper dive – an extended conversation.

Take for example the use of the iPhone and the Newton in your set of examples. One of your key points can be driven home even strongly by slightly rephrasing what you wrote, as follows, “For every Apple with their iPhone there’s an Apple with a Newton.”

What makes this particular example germane to the discussion is this: Jonathan Ive worked on the industrial design of both the iPhone and the Newton – an observation that is almost never mentioned, yet one that I think is really important.

One could respond by saying that, effectively, the Apple of the Newton and Scully was a different company. But there is still an important lesson to be gained: simply hiring a world-class designer into your company does not, in and of itself, make your company any more innovative.

But what about the current Apple of Jobs and Ive? How can we trust any purported lessons about innovation based on it if we only look at their successes? To me, their failures, and how they were managed, are as – if not more – enlightening than a study of their successes. How often do you hear or see informed commentary that speaks to the “hockey-puck” mouse on the original bondo blue iMac (I keep one hanging in my office), or the G4 Cube?

I mention this not to belittle Apple. Just the opposite. I firmly believe that failure is essential to innovation. If you don’t have periodic failure, you are almost certainly not pushing hard enough. You are simply not taking the risk that is part and parcel of great innovation. It is how you handle such risk, and the periodic failures, that is so important for an innovative company to succeed. For example, look how fast those round (move your hand up, watch your cursor go left) mice were replaced. If you don’t study the failures, you will miss this kind of thing, and blindly proceed under the assumption that great innovative companies bat 1000. That is a recipe for failure, not success.

Finally, in this world that celebrates the cult of the individual, and wants to believe in super-heroes, in innovation in technology, we tend to believe that great innovation grows out of a vacuum. This, again, is a reason to push beyond the surface in studying any single company’s performance and practice, insofar as innovation is concerned.

In my opinion, we need to get far better at assessing innovation in technology the same way that we do in music or painting, for example. Everybody knew the roots that Jimi Hendrix drew on in his music. That enhanced, rather than detracted from our appreciation of his innovative playing. One could say the same thing for any great painter, architect, film-maker, etc. No literate person would delude themselves that the whole thing came out of their head.

Yet, this is largely how far too much writing about technology is approached. As a test, see how many articles about the iPhone discuss it in terms of the world’s first smart phone, the 1993 Simon, developed jointly by IBM and Bell South? Compare the approach of the iPod Mini with that of the 1928 release of the Vanity Kodak camera, designed by Walter Dorwin Teague. Likewise, look at the designs the Dieter Rams did for Braun in the 1950’s and 60’s and compare it to numerous features in the iPod and iMac lines. The point is this: These and other examples represent the licks that Jonathan Ive was riffing on. They are to him what Muddy Waters, among others, was to Jimi Hendrix. Any discussion about design thinking that does not embrace this aspect of great design and the design process is incomplete. And, rather than take away from either Jonathan or Jimi, the more one understands this aspect of the process, the more one learns from, enjoys, and respects their work.

In a way, the message about innovation that is too often lost is this: Stop trying to be so damn original. Innovation is as much about prospecting for oldies but goodies as it is about invention. Look at it this way: if it is good enough for Jimi and Jonathan, then it is certainly okay for you and me.

But, without careful case studies of potent examples, we will miss this. Overall, this is why the term “design thinking” is so misleading. The very term suggests that it is a cognitive activity (“thinking”), when it is as much, or more, a cultural one.

In that light, I really like good writing that makes me think. That is why I liked your piece so much. The above is what it prompted. Perhaps in this collective act, itself, we have our own case study: one that shows illustrates that precious link between the cognitive and the social.

Thanks. Nice piece.

I like this piece in that it does a nice analysis, and at the same time, opens the door for a deeper dive – an extended conversation.

Take for example the use of the iPhone and the Newton in your set of examples. One of your key points can be driven home even strongly by slightly rephrasing what you wrote, as follows, “For every Apple with their iPhone there’s an Apple with a Newton.”

What makes this particular example germane to the discussion is this: Jonathan Ive worked on the industrial design of both the iPhone and the Newton – an observation that is almost never mentioned, yet one that I think is really important.

One could respond by saying that, effectively, the Apple of the Newton and Scully was a different company. But there is still an important lesson to be gained: simply hiring a world-class designer into your company does not, in and of itself, make your company any more innovative.

But what about the current Apple of Jobs and Ive? How can we trust any purported lessons about innovation based on it if we only look at their successes? To me, their failures, and how they were managed, are as – if not more – enlightening than a study of their successes. How often do you hear or see informed commentary that speaks to the “hockey-puck” mouse on the original bondo blue iMac (I keep one hanging in my office), or the G4 Cube?

I mention this not to belittle Apple. Just the opposite. I firmly believe that failure is essential to innovation. If you don’t have periodic failure, you are almost certainly not pushing hard enough. You are simply not taking the risk that is part and parcel of great innovation. It is how you handle such risk, and the periodic failures, that is so important for an innovative company to succeed. For example, look how fast those round (move your hand up, watch your cursor go left) mice were replaced. If you don’t study the failures, you will miss this kind of thing, and blindly proceed under the assumption that great innovative companies bat 1000. That is a recipe for failure, not success.

Finally, in this world that celebrates the cult of the individual, and wants to believe in super-heroes, in innovation in technology, we tend to believe that great innovation grows out of a vacuum. This, again, is a reason to push beyond the surface in studying any single company’s performance and practice, insofar as innovation is concerned.

In my opinion, we need to get far better at assessing innovation in technology the same way that we do in music or painting, for example. Everybody knew the roots that Jimi Hendrix drew on in his music. That enhanced, rather than detracted from our appreciation of his innovative playing. One could say the same thing for any great painter, architect, film-maker, etc. No literate person would delude themselves that the whole thing came out of their head.

Yet, this is largely how far too much writing about technology is approached. As a test, see how many articles about the iPhone discuss it in terms of the world’s first smart phone, the 1993 Simon, developed jointly by IBM and Bell South? Compare the approach of the iPod Mini with that of the 1928 release of the Vanity Kodak camera, designed by Walter Dorwin Teague. Likewise, look at the designs the Dieter Rams did for Braun in the 1950’s and 60’s and compare it to numerous features in the iPod and iMac lines. The point is this: These and other examples represent the licks that Jonathan Ive was riffing on. They are to him what Muddy Waters, among others, was to Jimi Hendrix. Any discussion about design thinking that does not embrace this aspect of great design and the design process is incomplete. And, rather than take away from either Jonathan or Jimi, the more one understands this aspect of the process, the more one learns from, enjoys, and respects their work.

In a way, the message about innovation that is too often lost is this: Stop trying to be so damn original. Innovation is as much about prospecting for oldies but goodies as it is about invention. Look at it this way: if it is good enough for Jimi and Jonathan, then it is certainly okay for you and me.

But, without careful case studies of potent examples, we will miss this. Overall, this is why the term “design thinking” is so misleading. The very term suggests that it is a cognitive activity (“thinking”), when it is as much, or more, a cultural one.

In that light, I really like good writing that makes me think. That is why I liked your piece so much. The above is what it prompted. Perhaps in this collective act, itself, we have our own case study: one that shows illustrates that precious link between the cognitive and the social.

Thanks. Nice piece.

We seem to be saying the same thing then 🙂

I must agree with your premiss that innovation is a cultural, rather than a cognitive, activity. As I commented in another blog post:

He was obviously talking of the cultural approach that both Jimi Hendrix and Jonathan Ive take to their work. (And which I hope I take too.) The key is to make it an institutional culture: Apple with the iPod rather than Apple with the Newton, as you quite rightly point out.

Implicit in this is the acceptance of failure. Or, as economists are want to say, “if you don’t fail occasionally, then your not optimising”. You need to be willing to try something different, even when popular opinion is against you. I remember when the first MacBook was released (just to stick with the Apple motif, and date myself) where the keyboard was near the hinge rather than away from it. The reviewers all laughed at Apple, but history is now laughing at the reviewers. (And many of these reviewers also said the iPhone would fail.) If you want the hits, then you need to risk the misses.

It’s interesting to consider the current startup movement in this light: a movement where (a first) failure is considered a badge of honour. But with the cost of entry so low (you can start something of a mid-sized credit card these days), is seems that these failures are not meaningful. It’s more like playing the pokies/one-armed-bandits. I put a dollar in and pull the lever, and then repeat until I either hit the jackpot or run out of dollars. Most people run out of cash, while the few that hit the jackpot are lauded as gods when, really, they were just lucky. (It’s great that they were lucky, but let’s admit that it was luck rather than genius that got them there.)

The cult of the individual, for me, is often a symptom of the eternal quest for the silver bullet. “If I buy this, then all will come good.” The Apple story is interesting: was the difference between the iPod and the Newton Steve Jobs, something else, or a combination? People flock to those individuals who they think will succeed. I’m sure that Mr Ives gets a job offer a day, but could he have the same level of success in an environment other than Apple? VCs are particularly notorious for this hero worship.

Twitter is a great example all of this in action. It cost little to start and, despite what the founders like to claim, there doesn’t seem to be a grand plan. The fact that they had done something before meant that they had more than a credit card available to kick-start the company, and they could also more easily attract funding. They’ve done the obvious things to make money (sell access to the data and, just wait for it, the personal information they have), but are yet to prove that they’ll provide a return on investment. (And the VCs have little to say other than “they’re smart, they’ll be able to do it”.) Twitter seems to spend most of its time adding features that advertisers like, but which the community ignores. Most of the innovation is from the community, with people finding interesting ways to use the service, rather than from Twitter itself.

Unfortunately I don’t think we’re ever going to overcome the cult of the individual / desire for the silver bullet. It’s probably a symptom of the competitive culture which dominates society today. We want the quick fix which provides the sure win. What if the key to innovation is not to be competitive? Is that what we should be looking for in these case studies: a playfulness and desire to experiment, the drive to be better was what we do, without the need to “be the biggest and/or best”. Obliquity.

Another great quote from my guitar teacher was something like:

Which is really just another way of saying “innovation is a cultural activity” 🙂

[…] 1. What is innovation? @ PEG↑2. Kogan↑ AKPC_IDS += "2396,";Related posts: […]