We have a new essay published by Deloitte Insights, Negotiating the digital-ready-organisation, a collaboration with Alex Bennett at NTT. This builds on our previous work on the transition to working digitally, Reconstructing the workplace, by trying to imagine what this future workplace might look like.

Continue readingCategory: Technology and its malcontents

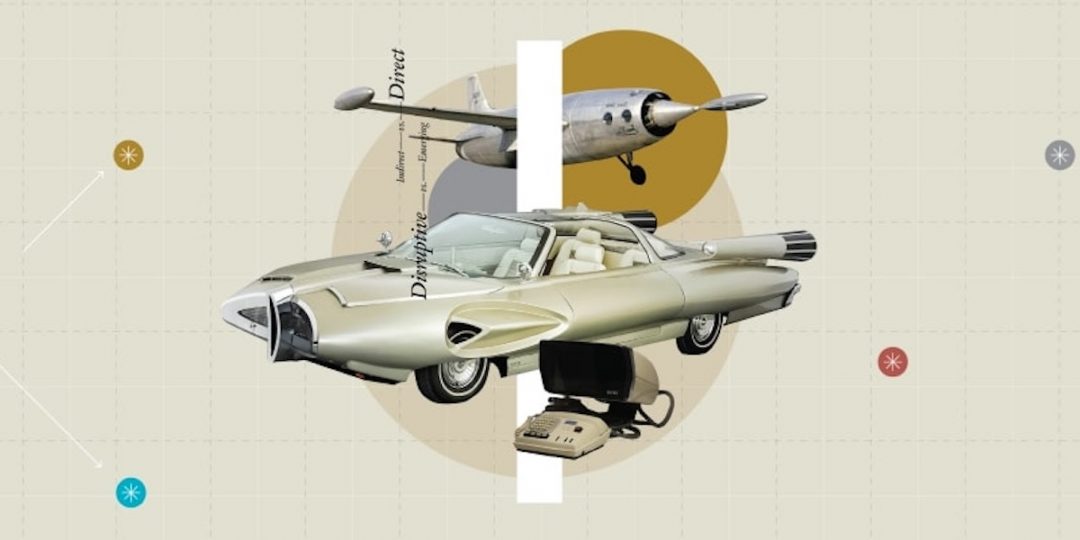

The real landscape of technology-enabled opportunity

We have a new essay published by Deloitte Insights, The real landscape of technology-enabled opportunity, where we look at how technology disrupts markets and society, creating opportunity.

Continue readingThe digital-ready workplace

We have a new essay published in Deloitte Insights, The digital-ready workplace: Supercharging digital teams in the future of work, a collaboration with Rosemary Stockdale from Griffith Business School and Tim Patston from UniSA STEM at the University of South Australia.

Most (if not all) research groups have done a survey on the affect working from home has had—this is ours, though it’s ended up in a different place. We start by trying to understand the relative merits of a push or pull approach to support workers during the transition, where push is the usual “give them the tools and training we think they’ll need” while pull is empower and support workers in finding their own tools. Generally, a push approach works well when the challenge is understood beforehand, while a pull approach is better when the challenge is not well understood as it enables workers to adapt. We’d heard anecdotal stories that firms had taken different approaches, and we were wondering how the relative benefits and problems stacked up. What we discovered, once the data started coming in, was that we were asking the wrong question.

Continue readingThe digital economy

A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of being on the panel for Blockchain and the Digital Economy at ADC’s Leadership Forum. The session outline led with three questions:

- How has 2020 accelerated the acceptance of the digital economy?

- Is blockchain fulfilling its promise as the new universal disruptor?

- How real is the role of cryptocurrencies as the new universal store of value?

It’s a large topic and an important one, as if we’re to address challenges such as growing inequality then we need to find a way to make the economy work for all of us, rather than just some of us.

Unfortunately, as too often happens, adding blockchain to a topic results in blockchain dominating the discussion with other interesting ideas ignored. Blockchain is quickly positioned as the solution and all other ways of framing (and understanding) the problems we face are ignored. This panel was no different in this regard.

Some of the ideas that would have been relevant in a broader discussion are things that I’ve been exploring for a while. Before the panel I’d pulled together an outline of the argument as to why our future is not “the digital economy”, but something much more interesting, and which creates more opportunity and freedom to act in addressing the challenges we’re facing. Rather than let a good outline go to waste I thought I’d build it out a little and publish it here.

Continue readingA moral license for AI

We have a new essay published in Deloitte Insights, A moral license for AI: Ethics as a dialogue between firms and communities. This collaboration with CSIRO’s Data61 looks into the challenge of creating ethical AI, picking apart the problems and proposing a way forward. There’s a launch event on the 2nd of September, 2020, which you can register for via Zoom.

Continue readingThe new division of labor

I, along with Alan Marshall and Robert Hillard, have a new essay published by Deloitte Insights – The new division of labor: On our evolving relationship with technology. This is the latest in an informal series that looks into how artificial intelligence (AI) is changing work. The other essays (should you be interested) are Cognitive collaboration, Reconstructing work and Reconstructing jobs.

Over the last few essays we’ve argued that humans and AI might both think but they think differently, though in complimentary ways, and if we’re to make the most of these differences we need to approach work differently. This was founded on the realisation that there is no skill – when construed within a task – that is unique to humans. Reconstructing work proposed that rather than thinking about work in terms of products, processes and tasks, it might be more productive to approach human work as a process of discovering what problems need to be solved, with automation doing the problem solving. Reconstructing jobs took this a step further and explored how jobs might change if we’re to make the most of both human and AI-powered machine using this approach, rather than simply using the machine to replace humans.

This new essay, The new division of labour, looks at what is holding us back. It’s common to focus on what’s known as the “skills gap”, the gap between the knowledge and skills the worker has and those required by the new technology. What’s often forgotten is that there’s also an emotional angle. The introduction of the word processor, for example, streamlined the production of business correspondence, but only after managers became comfortable taking on the responsibility of preparing their own correspondence. (And there’s still a few senior managers around who have their emails printed out so that they can draft a reply on the back for their assistant to type.) Social norms and attitudes often need to change before a technology’s full potential can be realised.

Continue readingDigitalizing the construction industry: A case study in complex disruption

I, along with a Robert Hillard and Peter Williams, have a new essay published by Deloitte Insights, Digitalizing the construction industry: A case study in […]

Continue readingYour next future

I and a coauthor have a new report out on DU Press: Your next future: Capitalising on disruptive change. Disruption is something we’d been puzzling for […]

Continue readingCryptocurrencies are problems, not features

CBA announced an Ethereum-based bond market solution[ref]James Eyers (24 Jan 2017), Commonwealth Bank puts government bonds on a blockchain, Australia Financial Review.[/ref]) It’s the usual sort of […]

Continue readingYou can’t democratise trust

I have a new post on the Deloitte Digital blog. There’s been a lot of talk about using technology to democratise trust, and much of it shows […]

Continue reading