Why Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman Explains Our Current Expertise Crisis

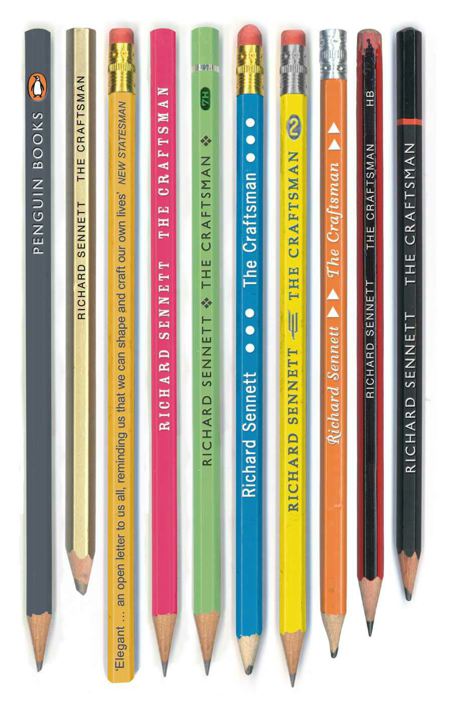

Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. Penguin, 2009.

Why do expert predictions keep failing while practical adaptations keep succeeding?

I’ve been tracking this pattern across domains: AI researchers confident about artificial general intelligence while workers quietly discover ChatGPT helps structure client presentations; fusion physicists announcing breakthroughs while the technology remains perpetually “almost ready”; policy experts debating digital transformation frameworks while small businesses just start using whatever tools solve Tuesday’s problems.

The disconnect isn’t accidental. It reveals something fundamental about how knowledge actually develops versus how we think it should. And Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman, published in 2009, provides the clearest framework I’ve found for understanding why this split keeps widening, and why it matters more than we realize.

The Head-Hand Split

Sennett’s central insight is deceptively simple: we’ve created a false opposition between thinking and making, between abstract knowledge and embodied skill. What he calls the “intelligent hand” represents a different kind of understanding: knowledge that emerges through sustained engagement with resistant materials, tools, and problems.

The craftsman develops expertise not by accumulating theoretical frameworks but through thousands of hours of responsive adjustment to how materials actually behave. A skilled carpenter doesn’t just know wood grain patterns abstractly; they feel how different woods respond to pressure, understand through touch when a joint is properly seated, develop intuitive timing for when glue has reached the right tackiness.

This embodied knowledge can’t be fully abstracted without loss. Try explaining to someone how to ride a bicycle using only words, or capture a master chef’s understanding of when bread dough has been kneaded enough. The knowledge exists in the interaction between person, tool, and material: not in any individual component.

But here’s what makes Sennett’s analysis particularly relevant now: he shows how institutional pressures systematically exclude this embodied knowledge when it threatens clean narratives or challenges abstract authority.

The Pattern in Practice

Consider the AI researcher I described elsewhere1 who became confused when confronted with evidence that intelligence emerges through networks rather than individual capability. When presented with detailed examples and research citations, their final response was: “Are you using AI to write this? Is this a bit?”

This isn’t intellectual failure; it’s what happens when someone tries to navigate new reality using old conceptual tools. The researcher was operating from a framework where intelligence is a measurable property that entities possess. The commenter was working from an understanding of intelligence as distributed, emergent, relational. Both perspectives explain some phenomena well, but only one was grounded in practical experience with how these systems actually function.

Sennett would recognize this immediately. It’s the same pattern he identifies when examining how the “eye of the master” emerged during industrialization. As skilled labor became abstracted and systematised, supervisory oversight developed to monitor and control what could no longer be directly understood. But the eye of the master only works when there’s consensus about what should be seen and how to interpret those observations.

The AI governance debates reveal the same dynamic. While researchers debate abstract capabilities and policymakers design regulation around hypothetical risks, there’s already a practical revolution happening. The 15-year-old using image generators for movie storyboards, the teacher discovering ChatGPT helps with lesson planning, the paralegal finding AI drafts better contracts than junior associates—they’re developing craft knowledge about how these systems actually work.

But this practical knowledge gets systematically excluded from official discussions. It’s too messy, too context-dependent, too difficult to abstract into policy frameworks.

This pattern has deep historical roots. In Leviathan and the Air-Pump,2 Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer show how Robert Boyle’s experimental demonstrations at the 1660s Royal Society created what became the template for modern expertise: witnessed consensus among gentlemen observers, with the craftsmen who built and operated the instruments systematically erased from the performance.

Boyle’s air-pump experiments didn’t just demonstrate natural phenomena—they created a new way of producing authoritative knowledge through theatrical consensus. The pump made visible effects that lay beyond ordinary perception, but this required elaborate staging. Gentlemanly witnesses agreed on what they had seen, their consensus became truth, and royal patronage made the performance politically safe by making it appear politically neutral.

Most crucially, the performance required systematic forgetting. The instrument-makers possessed irreplaceable knowledge about materials, failure modes, and how to make the apparatus actually work. But their embodied expertise couldn’t be gentlemanly, so it was erased from the public demonstration. The air-pump’s authority depended on appearing to speak for nature directly, not through the mediation of craftsmen’s hands.

Sennett shows how this exclusion of craft knowledge has persisted and intensified. The people developing actual fluency with AI tools find their understanding dismissed by the very experts most confident about the technology’s trajectory, just as Boyle’s instrument-makers were written out of experimental philosophy. The performance of expertise requires clean narratives that embodied knowledge threatens to complicate.

The High Modernist Trap

This connects to a deeper pattern that James C. Scott analyzed in Seeing Like a State:3 how abstract, simplified models systematically exclude the contextual knowledge that makes complex systems actually work. Scott shows how high modernist schemes—scientific forestry, planned cities, collectivized agriculture—fail because they replace local, practical wisdom (what he calls “metis”) with legible but fragile abstractions.

Sennett’s craftsman possesses exactly what Scott means by metis: contextual knowledge that emerges through sustained engagement with how things actually behave. The carpenter’s understanding of wood grain, the blacksmith’s feel for metal temperature, the baker’s timing for fermentation—this knowledge can’t be fully abstracted into formal rules without crucial information being lost.

The renewable energy transition reveals this pattern operating at infrastructure scale. Traditional electrical grids embodied a kind of collective metis: synchronous generators that “saw” system state directly through rotating mass, grid operators who understood failure modes through decades of experience, informal networks of engineers who knew which equipment was actually reliable despite what the specifications claimed.

The smart grid project attempts to replace this illegible but robust system with something cleaner and more controllable: standardised digital interfaces, algorithmic optimisation, centralised monitoring. This transition from direct to indirect perception creates exactly the coordination failures Scott predicted.

When Spain’s grid collapsed in April 2025, the cascade of competing explanations—utilities blamed operators, operators blamed generators, official probes blamed everyone—revealed what happens when simplified, legible systems fail. Multiple competing authorities emerged because no single model could capture what the illegible traditional system had been doing automatically.

The grid engineers who warned about renewable integration challenges—loss of inertia, frequency stability problems, voltage control issues—possessed irreplaceable metis about how these systems actually behave. But their knowledge was systematically excluded from policy discussions because it threatened clean institutional narratives about the energy transition. Like Scott’s traditional farmers whose sophisticated understanding of local ecosystems was dismissed by agricultural modernizers, the engineers’ embodied expertise was seen as politically inconvenient rather than technically essential.

Thomas Hobbes opposed Boyle’s experimental method not on technical grounds but because he foresaw its political consequences. If truth becomes a matter of staged performance rather than sovereign decree, what happens when multiple stages compete for the same audience? Hobbes predicted the war of all against all would relocate to the witness stand.

His diagnosis was remarkably astute. Today we have exactly what he feared: peer review competing with preprints competing with energy Twitter competing with government agencies, each staging truth for different audiences with equal confidence but incompatible frameworks. Google, ChatGPT, grid operators, and standards bodies all perform expertise using Boyle’s theatrical template, but the consensus-forming performance has escaped institutional control and proliferated everywhere.

But Hobbes missed the recursive trap. He feared competing authorities but didn’t foresee that attempts to restore unified authority would only accelerate fragmentation. We demand more expertise precisely because we trust it less—and each demand for better expertise makes expertise more political. When expertise becomes contested, the response is always to call for more technical solutions, which inevitably makes science more political.

The result is what Gil Eyal calls the “pushmi-pullyu” of modern expertise:4 simultaneous reliance and skepticism, escalating together. Every attempt to fix the legitimacy crisis through better institutional performance only deepens the crisis by creating new stages for contestation.

Beyond the Performance

If consensus is impossible and authority is permanently contested, how do we maintain contact with reality? Sennett suggests we need what might be called “hybrid perception”—arrangements that combine embodied knowledge with computational augmentation without privileging either exclusively.

Consider how modern aviation actually works. Commercial pilots combine instrument readings with embodied feel for aircraft behavior—understanding how a plane “wants” to fly that can’t be captured in flight management computers. Air traffic controllers mix radar data with experiential knowledge of weather patterns and traffic flows. Neither purely human judgment nor purely automated systems can handle the complexity safely. The effectiveness emerges from dynamic interaction between direct embodied knowledge and indirect computational analysis.

This suggests a different approach to expertise: systems that work despite permanent disagreement about what they mean or who’s in charge. The goal isn’t eliminating interpretive disputes but designing coordination that functions anyway.

Emergency responders already do this. Firefighters and paramedics combine years of embodied experience with real-time digital information. They don’t wait for expert consensus about optimal strategies—they respond to immediate conditions using hybrid perception that integrates direct sensory contact with digital augmentation.

The Craftsman’s Relevance

Sennett’s framework helps explain why the practical adaptations succeed while the expert predictions fail. The consultant who discovers AI helps structure client presentations isn’t implementing a theory about artificial intelligence—they’re developing craft knowledge through sustained engagement with the tool’s actual capabilities and limitations. They learn through repetition, adjustment, failure, and refinement—exactly the process Sennett describes.

Meanwhile, the experts debating AI safety frameworks operate in pure abstraction, divorced from the daily practice of making these systems work reliably. Their knowledge, however sophisticated, lacks the grounding that comes from sustained engagement with resistant materials.

This isn’t anti-intellectual. Sennett shows how the best craftspeople combine embodied skill with reflective analysis. The master carpenter understands both the feel of properly seasoned wood and the principles of structural engineering. But the integration happens through practice, not through choosing one mode of knowing over another.

The Craftsman matters now because we’re living through a moment when abstract expertise keeps failing while practical knowledge keeps succeeding, but we lack conceptual tools to understand why. Sennett provides those tools—not as nostalgic romance for pre-industrial craft production, but as analysis of how knowledge actually develops in complex systems.

The book reveals that our expertise crisis isn’t really about information or credibility. It’s about the systematic exclusion of embodied knowledge from institutional decision-making. Until we create arrangements that honor both abstract analysis and craft wisdom, we’ll keep getting expert predictions that miss reality while practical adaptations quietly build the future.

The revolution isn’t replacement of old expertise with new expertise. It’s learning to coordinate effectively despite permanent disagreement about what we’re building or why it matters. Sennett shows us how: through patient attention to what actually works, sustained engagement with resistant materials, and respect for the intelligent hand.

4/5. Essential reading for anyone trying to understand why expertise keeps fragmenting while practical knowledge keeps succeeding.

- Evans-Greenwood, Peter. “The Collapse of Dominant Stories.” Substack newsletter. The Puzzle and Its Pieces, August 19, 2025. https://thepuzzleanditspieces.substack.com/p/the-collapse-of-dominant-stories. ↩︎

- Shapin, Steven, Simon Schaffer, and Steven Shapin. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life: With a New Introduction by the Authors. Princeton University Press, 2011. ↩︎

- Scott, James C. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Nachdr. Yale Agrarian Studies. Yale Univ. Press, 1999. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300078152/seeing-state. ↩︎

- pp110,180-181 in Eyal, Gil. The Crisis of Expertise. Polity, 2019. ↩︎