The AI research community is having another moment with world models. Quanta Magazine’s recent piece1 traces the concept back to Kenneth Craik’s 1943 insight about organisms carrying “small-scale models” of reality in their heads. Now, with LLMs showing unexpected capabilities, researchers are betting that better world models might be the key to AGI.

But there’s something revealing happening in this revival. The more we try to find coherent world models in current AI systems, the more we discover what researchers call “bags of heuristics”—disconnected rules that work in aggregate but don’t form unified understanding. When MIT researchers tested an LLM that could navigate Manhattan perfectly, it collapsed when just 1% of streets were barricaded at random. No coherent map, just an elaborate patchwork of corner-by-corner shortcuts.

This raises the grounding question: what keeps intelligence honest?

The Anchoring Problem

Current AI systems work purely through symbolic manipulation—building statistical patterns and trying to map representations onto other representations. It’s modelling all the way down, with no foundational anchor in direct experience.

Human cognition appears to work differently, though not in the simple way the direct vs. indirect perception debate suggests. We likely use both modes: direct perceptual coupling with the world and internal (indirect) models for planning and abstract reasoning. But here’s the crucial difference: our models are tethered to raw experience—constantly stress-tested by the world.

When you walk into a familiar room in the dark, you don’t consult an internal floor plan. Your body knows the space directly. But you can also mentally rotate that room, imagine rearranging the furniture, or describe it to someone else. The modelling capacity emerges from and remains grounded in direct perceptual coupling.

This suggests that human intelligence isn’t just about having better internal representations—it’s about having representations that stay tethered to something beyond themselves. What psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan called our access to “the Real”—that which resists complete symbolisation and keeps our models incomplete, dynamic, responsive to what exceeds our current understanding.

The Floating Symbol Problem

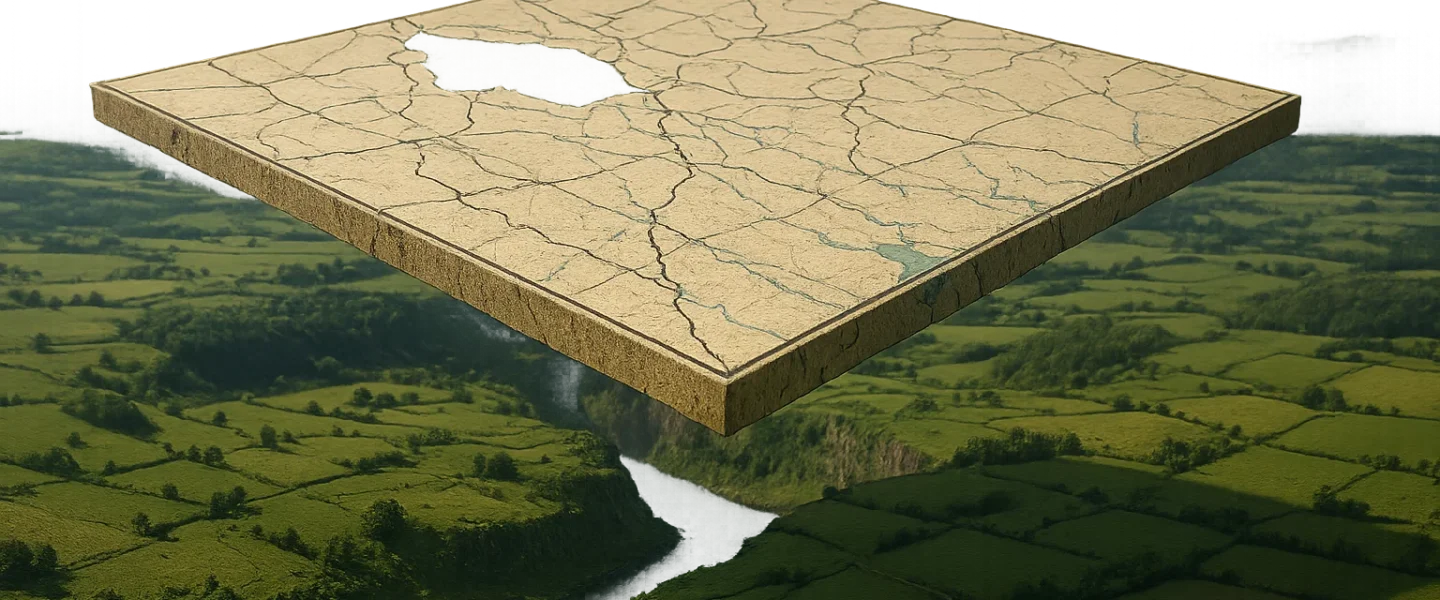

AI systems, operating purely in the symbolic realm, lack this anchoring tension. Their world models, no matter how sophisticated, remain representations of representations—symbols adrift, referring only to one another.

This creates what we might call the floating symbol problem. Without anchor points in immediate experience, AI representations can become internally coherent while losing connection to the realities they’re supposed to model. The Manhattan navigation example is perfect: the system developed an elaborate internal consistency that worked until reality threw it a curveball it had never symbolically encountered. Picture the LLM at that instant: still fluent, still confident, cheerfully directing you down a street that no longer exists—like a GPS that’s never seen potholes. This is also where LLM hallucinations come from (though I hear that they’re increasingly being called ‘confabulations’, which is a better term).

The irony is that in trying to make AI more human-like through better world models, researchers might be highlighting exactly what makes human intelligence distinctive: not just our capacity for representation, but our hybrid architecture where symbolic thinking remains grounded in non-symbolic engagement.

Beyond the False Choice

This reframes the AGI question. If intelligence requires this hybrid architecture—direct coupling and flexible modelling anchored by that coupling—then artificial general intelligence might not be impossible, but it’s probably not achievable through a symbol-centric approach, no matter how sophisticated. This rules out both symbolic AI (rules etc) and pattern-based AI (neural networks etc) as both rely on symbols, both understand to experience.

The path forward might require fundamentally different approaches: systems that can engage with their environments in ways that aren’t mediated entirely through representations. Not just better world models, but systems that feel the world the way a hand feels heat—directly, without a map.

The world model revival in AI research isn’t wrong to look for internal representations. But it might be asking the wrong question: instead of “How do we build better models?” we might need to ask “What anchors models to reality in the first place?”

That’s not just a technical question—it’s a philosophical one about the nature of meaning, understanding, and intelligence itself. And it suggests the most interesting work might be happening at the intersection of cognitive science, phenomenology, and embodied AI rather than in the race for bigger, more sophisticated language models.

After decades of AI research, we’re still discovering what we don’t know about intelligence. That’s not a bug—it’s where the real insights begin.

- Pavlus, J. (2025, September 2). ‘World Models,’ an old idea in AI, mount a comeback. Quanta Magazine. https://www.quantamagazine.org/world-models-an-old-idea-in-ai-mount-a-comeback-20250902/ ↩︎